As someone

who grew up on the internet, I credit it as one of the most important

influences on who I am today. I had a computer with internet access in

my bedroom from the age of 13. It gave me access to a lot of things

which were totally inappropriate for a young teenager, but it was OK.

The culture, politics, and interpersonal relationships which I consider

to be central to my identity were shaped by the internet, in ways that I

have always considered to be beneficial to me personally. I have always

been a critical proponent of the internet and everything it has

brought, and broadly considered it to be emancipatory and beneficial. I

state this at the outset because thinking through the implications of

the problem I am going to describe troubles my own assumptions and

prejudices in significant ways.

One

of the thus-far hypothetical questions I ask myself frequently is how I

would feel about my own children having the same kind of access to the

internet today. And I find the question increasingly difficult to

answer. I understand that this is a natural evolution of attitudes which

happens with age, and at some point this question might be a lot less

hypothetical. I don’t want to be a hypocrite about it. I would want my

kids to have the same opportunities to explore and grow and express

themselves as I did. I would like them to have that choice. And this

belief broadens into attitudes about the role of the internet in public

life as whole.

I’ve

also been aware for some time of the increasingly symbiotic

relationship between younger children and YouTube. I see kids engrossed

in screens all the time, in pushchairs and in restaurants, and there’s

always a bit of a Luddite twinge there, but I am not a parent, and I’m

not making parental judgments for or on anyone else. I’ve seen family

members and friend’s children plugged into Peppa Pig and nursery rhyme

videos, and it makes them happy and gives everyone a break, so OK.

But I don’t even have kids and right now I just want to burn the whole thing down.

Someone

or something or some combination of people and things is using YouTube

to systematically frighten, traumatise, and abuse children,

automatically and at scale, and it forces me to question my own beliefs

about the internet, at every level. Much of what I am going to

describe next has been covered elsewhere, although none of the

mainstream coverage I’ve seen has really grasped the implications of

what seems to be occurring.

To begin: Kid’s YouTube is definitely and markedly weird. I’ve been aware of its weirdness for some time. Last year, there were a number of articles

posted about the Surprise Egg craze. Surprise Eggs videos depict, often

at excruciating length, the process of unwrapping Kinder and other egg

toys. That’s it, but kids are captivated by them. There are thousands

and thousands of these videos and thousands and thousands, if not

millions, of children watching them.

From the article linked above:

The maker of my particular favorite videos is “Blu Toys Surprise Brinquedos & Juegos,” and since 2010 he seems to have accrued 3.7 million subscribers and just under 6 billion views for a kid-friendly channel entirely devoted to opening surprise eggs and unboxing toys. The video titles are a continuous pattern of obscure branded lines and tie-ins: “Surprise Play Doh Eggs Peppa Pig Stamper Cars Pocoyo Minecraft Smurfs Kinder Play Doh Sparkle Brilho,” “Cars Screamin’ Banshee Eats Lightning McQueen Disney Pixar,” “Disney Baby Pop Up Pals Easter Eggs SURPRISE.”

As I write this he has done a total of 4,426 videos and counting. With so many views — for comparison, Justin Bieber’s official channel has more than 10 billion views, while full-time YouTube celebrity PewDiePie has nearly 12 billion — it’s likely this man makes a living as a pair of gently murmuring hands that unwrap Kinder eggs. (Surprise-egg videos are all accompanied by pre-roll, and sometimes mid-video and ads.)

That

should give you some idea of just how odd the world of kids online

video is, and that list of video titles hints at the extraordinary range

and complexity of this situation. We’ll get into the latter in a

minute; for the moment know that it’s already very strange, if

apparently pretty harmless, out there.

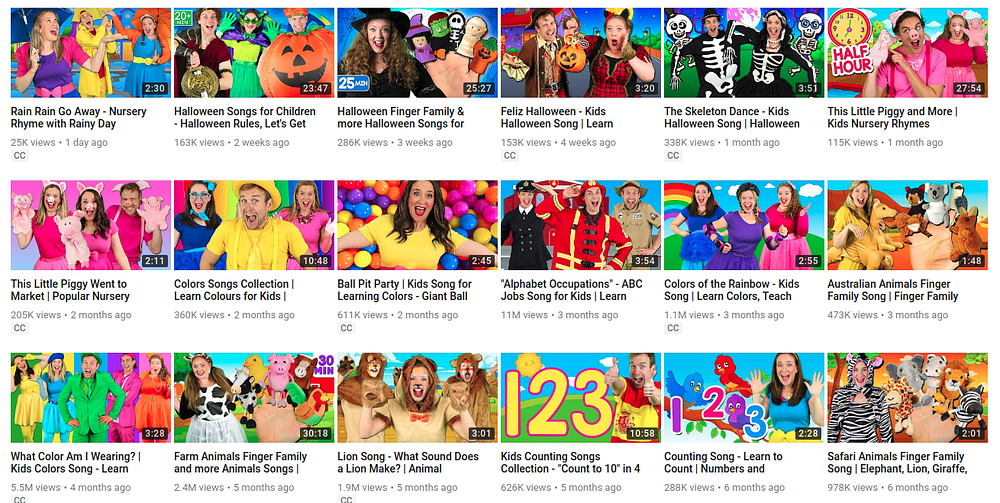

Another huge trope, especially the youngest children, is nursery rhyme videos.

Little Baby Bum, which made the above video, is the 7th most popular channel on YouTube. With just 515 videos, they have accrued 11.5 million subscribers and 13 billion views. Again,

there are questions as to the accuracy of these numbers, which I’ll get

into shortly, but the key point is that this is a huge, huge network

and industry.

On-demand

video is catnip to both parents and to children, and thus to content

creators and advertisers. Small children are mesmerised by these videos,

whether it’s familiar characters and songs, or simply bright colours

and soothing sounds. The length of many of these videos — one common

video tactic is to assemble many nursery rhyme or cartoon episodes into

hour+ compilations —and the way that length is marketed as part of the

video’s appeal, points to the amount of time some kids are spending with

them.

YouTube

broadcasters have thus developed a huge number of tactics to draw

parents’ and childrens’ attention to their videos, and the advertising

revenues that accompany them. The first of these tactics is simply to

copy and pirate other content. A simple search for “Peppa Pig” on

YouTube in my case yielded “About 10,400,000 results” and the front page

is almost entirely from the verified “Peppa Pig Official Channel”,

while one is from an unverified channel called Play Go Toys, which you really wouldn’t notice unless you were looking out for it:

Play Go Toys’ channel

consists of (I guess?) pirated Peppa Pig and other cartoons, videos of

toy unboxings (another kid magnet), and videos of, one supposes, the

channel owner’s own children. I am not alleging anything bad about Play

Go Toys; I am simply illustrating how the structure of YouTube

facilitates the delamination of content and author, and how this impacts

on our awareness and trust of its source.

As another blogger notes,

one of the traditional roles of branded content is that it is a trusted

source. Whether it’s Peppa Pig on children’s TV or a Disney movie,

whatever one’s feelings about the industrial model of entertainment

production, they are carefully produced and monitored so that kids are

essentially safe watching them, and can be trusted as such.

This no longer applies when brand and content are disassociated by the

platform, and so known and trusted content provides a seamless gateway

to unverified and potentially harmful content.

(Yes, this is the exact same process as the delamination of trusted news media on Facebook feeds and in Google results

that is currently wreaking such havoc on our cognitive and political

systems and I am not going to explicitly explore that relationship

further here, but it is obviously deeply significant.)

A

second way of increasing hits on videos is through keyword/hashtag

association, which is a whole dark art unto itself. When some trend,

such as Surprise Egg videos, reaches critical mass, content producers

pile onto it, creating thousands and thousands more of these videos in

every possible iteration. This is the origin of all the weird names in

the list above: branded content and nursery rhyme titles and “surprise

egg” all stuffed into the same word salad to capture search results,

sidebar placement, and “up next” autoplay rankings.

A striking example of the weirdness is the Finger Family videos

(harmless example embedded above). I have no idea where they came from

or the origin of the children’s rhyme at the core of the trope, but

there are at least 17 million versions of this currently on YouTube, and again they cover every possible genre, with billions and billions of aggregated views.

Once

again, the view numbers of these videos must be taken under serious

advisement. A huge number of these videos are essentially created by

bots and viewed by bots, and even commented on by bots. That is a whole

strange world in and of itself. But it shouldn’t obscure that there are

also many actual children, plugged into iphones and tablets, watching

these over and over again — in part accounting for the inflated view

numbers — learning to type basic search terms into the browser, or

simply mashing the sidebar to bring up another video.

What

I find somewhat disturbing about the proliferation of even (relatively)

normal kids videos is the impossibility of determining the degree of

automation which is at work here; how to parse out the gap between human

and machine. The example above, from a channel called Bounce Patrol Kids,

with almost two million subscribers, show this effect in action. It

posts professionally produced videos, with dedicated human actors, at

the rate of about one per week. Once again, I am not alleging anything

untoward about Bounce Patrol, which clearly follows in the footsteps of

pre-digital kid sensations like their fellow Australians The Wiggles.

And

yet, there is something weird about a group of people endlessly acting

out the implications of a combination of algorithmically generated

keywords: “Halloween Finger Family & more Halloween Songs for

Children | Kids Halloween Songs Collection”, “Australian Animals Finger

Family Song | Finger Family Nursery Rhymes”, “Farm Animals Finger Family

and more Animals Songs | Finger Family Collection - Learn Animals

Sounds”, “Safari Animals Finger Family Song | Elephant, Lion, Giraffe,

Zebra & Hippo! Wild Animals for kids”, “Superheroes Finger Family

and more Finger Family Songs! Superhero Finger Family Collection”,

“Batman Finger Family Song — Superheroes and Villains! Batman, Joker,

Riddler, Catwoman” and on and on and on. This is content production in

the age of algorithmic discovery — even if you’re a human, you have to

end up impersonating the machine.

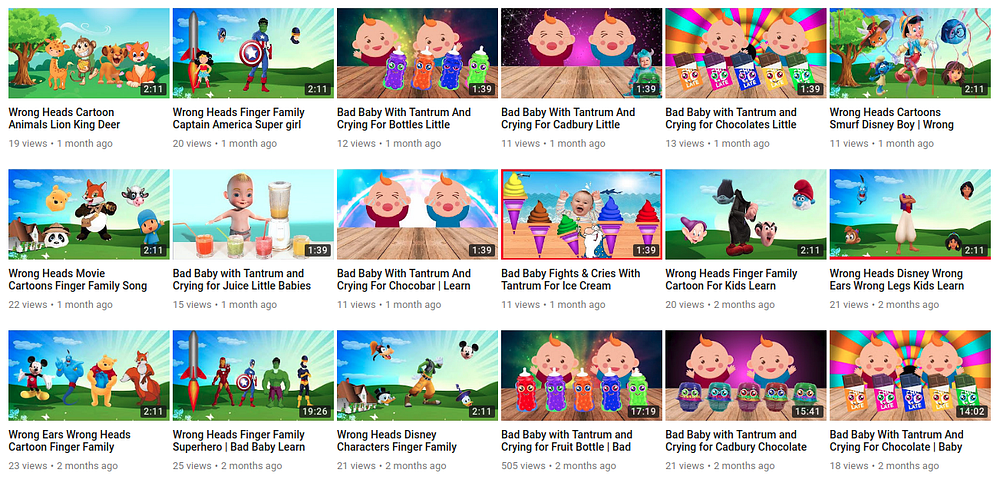

Other

channels do away with the human actors to create infinite

reconfigurable versions of the same videos over and over again. What is

occurring here is clearly automated. Stock animations, audio tracks, and

lists of keywords being assembled in their thousands to produce an

endless stream of videos. The above channel, Videogyan 3D Rhymes — Nursery Rhymes & Baby Songs,

posts several videos a week, in increasingly byzantine combinations of

keywords. They have almost five million subscribers — more than double

Bounce Patrol — although once again it’s impossible to know who or what

is actually racking up these millions and millions of views.

I’m

trying not to turn this essay into an endless list of examples, but

it’s important to grasp how vast this system is, and how indeterminate

its actions, process, and audience. It’s also international: there are

variations of Finger Family and Learn Colours videos for Tamil epics and Malaysian cartoons

which are unlikely to pop up in any Anglophone search results. This

very indeterminacy and reach is key to its existence, and its

implications. Its dimensionality makes it difficult to grasp, or even to

really think about.

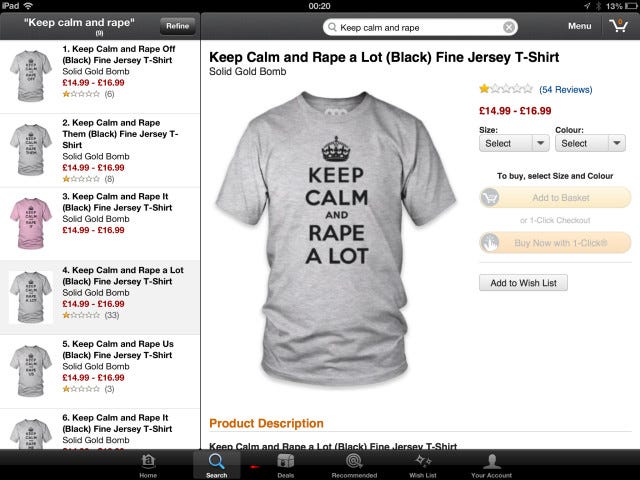

We’ve

encountered pretty clear examples of the disturbing outcomes of full

automation before — some of which have been thankfully leavened with a

dark kind of humour, others not so much. Much has been made of the

algorithmic interbreeding of stock photo libraries and on-demand

production of everything from tshirts to coffee mugs to infant onesies

and cell phone covers. The above example, available until recently on

Amazon, is one such case, and the story of how it came to occur is fascinating and weird but essentially comprehensible.

Nobody set out to create phone cases with drugs and medical equipment

on them, it was just a deeply weird mathematical/probabilistic outcome.

The fact that it took a while to notice might ring some alarm bells

however.

Likewise, the case of the “Keep Calm and Rape A Lot” tshirts

(along with the “Keep Calm and Knife Her” and “Keep Calm and Hit Her”

ones) is depressing and distressing but comprehensible. Nobody set out

to create these shirts: they just paired an unchecked list of verbs and

pronouns with an online image generator. It’s quite possible that none

of these shirts ever physically existed, were ever purchased or worn,

and thus that no harm was done. Once again though, the people creating

this content failed to notice, and neither did the distributor. They literally had no idea what they were doing.

What

I will argue, on the basis of these cases and of those I’m going to

describe further, is that the scale and logic of the system is complicit

in these outputs, and requires us to think through their implications.

(Also

again: I’m not going to dig into the wider social implications of such

processes outside the scope of what I am writing about here, but it’s

clear that one can draw a clear line from examples such as these to

pressing contemporary issues such as racial and gender

bias in big data and machine intelligence-driven systems, which require

urgent attention but in the same manner do not have anything resembling

easy or even preferable solutions.)

Let’s

look at just one video among the piles of kid videos, and try to parse

out where it comes from. It’s important to stress that I didn’t set out

to find this particular video: it appeared organically and highly ranked

in a search for ‘finger family’ in an incognito browser window

(i.e. it should not have been influenced by previous searches). This

automation takes us to very, very strange places, and at this point the

rabbithole is so deep that it’s impossible to know how such a thing came

into being.

Once again, a content warning: this video is not inappropriate in any way, but it is decidedly off, and contains elements which might trouble anyone. It’s

very mild on the scale of such things, but. I describe it below if you

don’t want to watch it and head down that road. This warning will recur.

The above video is entitled Wrong Heads Disney Wrong Ears Wrong Legs Kids Learn Colors Finger Family 2017 Nursery Rhymes.

The title alone confirms its automated provenance. I have no idea where

the “Wrong Heads” trope originates, but I can imagine, as with the

Finger Family Song, that somewhere there is a totally original and

harmless version that made enough kids laugh that it started to climb

the algorithmic rankings until it made it onto the word salad lists,

combining with Learn Colors, Finger Family, and Nursery Rhymes, and all

of these tropes — not merely as words but as images, processes, and

actions — to be mixed into what we see here.

The

video consists of a regular version of the Finger Family song played

over an animation of character heads and bodies from Disney’s Aladdin

swapping and intersecting. Again, this is weird but frankly no more than

the Surprise Egg videos or anything else kids watch. I get how innocent

it is. The offness creeps in

with the appearance of a non-Aladdin character —Agnes, the little girl

from Despicable Me. Agnes is the arbiter of the scene: when the heads

don’t match up, she cries, when they do, she cheers.

The video’s creator, BABYFUN TV

(screenshot above), has produced many similar videos. As many of the

Wrong Heads videos as I could bear to watch all work in exactly the same

way. The character Hope from Inside Out weeps through a Smurfs and Trolls head swap.

It goes on and on. I get the game, but the constant overlaying and

intermixing of different tropes starts to get inside you. BABYFUN TV

only has 170 subscribers and very low view rates, but then there are

thousands and thousands of channels like this. Numbers in the long tail aren’t significant in the abstract, but in their accumulation.

The

question becomes: how did this come to be? The “Bad Baby” trope also

present on BABYFUN TV features the same crying. While I find it

disturbing, I can understand how it might provide some of the rhythm or

cadence or relation to their own experience that actual babies are

attracted to in this content, although it has been warped and stretched

through algorithmic repetition and recombination in ways that I don’t

think anyone actually wants to happen.

[Edit, 21/11/2017: Following the publication of this article, the Toy Freaks channel was removed by YouTube as part of a widespread removal of contentious content.]

Toy Freaks is a hugely popular channel (68th on the platform)

which features a father and his two daughters playing out — or in some

cases perhaps originating — many of the tropes we’ve identified so far,

including “Bad Baby”, (previously embedded above). As well as nursery

rhymes and learning colours, Toy Freaks specialises in gross-out

situations, as well as activities which many, many viewers feel border

on abuse and exploitation, if not cross the line entirely, including

videos of the children vomiting and in pain. Toy Freaks is a YouTube

verified channel, whatever that means. (I think we know by now it means nothing useful.)

As

with Bounce Patrol Kids, however you feel about the content of these

videos, it feels impossible to know where the automation starts and

ends, who is coming up with the ideas and who is roleplaying them. In

turn, the amplification of tropes in popular, human-led channels such as

Toy Freaks leads to them being endlessly repeated across the network in

increasingly outlandish and distorted recombinations.

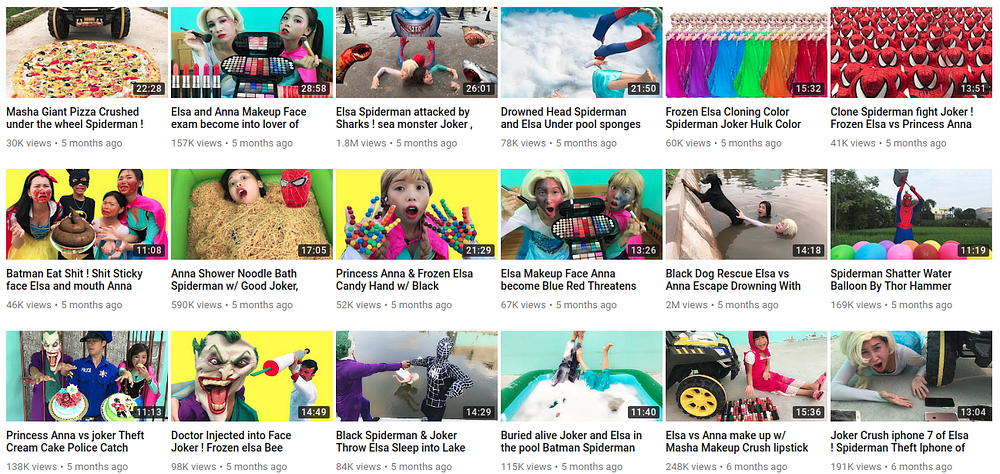

There’s

a second level of what I’m characterising as human-led videos which are

much more disturbing than the mostly distasteful activities of Toy

Freaks and their kin. Here is a relatively mild, but still upsetting

example:

A

step beyond the simply pirated Peppa Pig videos mentioned previously

are the knock-offs. These too seem to teem with violence. In the

official Peppa Pig videos, Peppa does indeed go to the dentist, and the

episode in which she does so seems to be popular — although,

confusingly, what appears to be the real episode

is only available on an unofficial channel. In the official timeline,

Peppa is appropriately reassured by a kindly dentist. In the version

above, she is basically tortured, before turning into a series of Iron

Man robots and performing the Learn Colours dance. A search for “peppa

pig dentist” returns the above video on the front page, and it only gets

worse from here.

[Edit, 21/11/2017:

the original video cited here has now been removed as part of YouTube’s

recent purge, although many similar videos remain on the platform.]

Disturbing Peppa Pig videos, which tend towards extreme violence and fear, with Peppa eating her father or drinking bleach, are, it turns out very widespread. They make up an entire YouTube subculture. Many are obviously parodies,

or even satires of themselves, in the pretty common style of the

internet’s outrageous, deliberately offensive kind. All the 4chan tropes

are there, the trolls are out, we know this.

In

the example above, the agency is less clear: the video starts with a

trollish Peppa parody, but later syncs into the kind of automated

repetition of tropes we’ve seen already. I don’t know which camp it

belongs to. Maybe it’s just trolls. I kind of hope it is. But I don’t

think so. Trolls don’t cover the intersection of human actors and more

automated examples further down the line. They’re at play here, but

they’re not the whole story.

I

suppose it’s naive not to see the deliberate versions of this coming,

but many are so close to the original, and so unsignposted — like the

dentist example — that many, many kids are watching them. I understand that most of them are not trying to mess kids up, not really, even though they are.

I’m

trying to understand why, as plainly and simply troubling as it is,

this is not a simple matter of “won’t somebody think of the children”

hand-wringing. Obviously this content is inappropriate, obviously there are bad actors out there, obviously some of these videos should be removed. Obviously

too this raises questions of fair use, appropriation, free speech and

so on. But reports which simply understand the problem through this lens

fail to fully grasp the mechanisms being deployed, and thus are

incapable of thinking its implications in totality, and responding

accordingly.

The New York Times, headlining their article on a subset of this issue “On YouTube Kids, Startling Videos Slip Past Filters”,

highlights the use of knock-off characters and nursery rhymes in

disturbing content, and frames it as a problem of moderation and

legislation. YouTube Kids, an official app which claims to be kid-safe

but is quite obviously not, is the problem identified, because it

wrongly engenders trust in users. An article in the British tabloid The

Sun, “Kids left traumatised after sick YouTube clips showing Peppa Pig characters with knives and guns appear on app for children”

takes the same line, with an added dose of right-wing technophobia and

self-righteousness. But both stories take at face value YouTube’s

assertions that these results are incredibly rare and quickly removed:

assertions utterly refuted by the proliferation of the stories

themselves, and the growing number of social media posts, largely by

concerned parents, from which they arise.

But

as with Toy Freaks, what is concerning to me about the Peppa videos is

how the obvious parodies and even the shadier knock-offs interact with

the legions of algorithmic content producers until it is completely

impossible to know what is going on. (“The creatures outside looked from

pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already

it was impossible to say which was which.”)

Here’s what is basically a version of Toy Freaks produced in Asia (screenshot above). Here’s one from Russia.

I don’t really want to use the term “human-led” any more about these

videos, although they contain all the same tropes and actual people

acting them out. I no longer have any idea what’s going on here and I

really don’t want to and I’m starting to think that that is kind of the

point. That’s part of why I’m starting to think about the deliberateness

of this all. There is a lot of effort going into making these. More

than spam revenue can generate — can it? Who’s writing these scripts,

editing these videos? Once again, I want to stress: this is still really mild, even funny stuff compared to a lot of what is out there.

Here are a few things which are disturbing me:

The

first is the level of horror and violence on display. Some of the times

it’s troll-y gross-out stuff; most of the time it seems deeper, and

more unconscious than that. The internet has a way of amplifying and

enabling many of our latent desires; in fact, it’s what it seems to do

best. I spend a lot of time arguing for

this tendency, with regards to human sexual freedom, individual

identity, and other issues. Here, and overwhelmingly it sometimes feels,

that tendency is itself a violent and destructive one.

The

second is the levels of exploitation, not of children because they are

children but of children because they are powerless. Automated reward

systems like YouTube algorithms necessitate exploitation in the same way

that capitalism necessitates exploitation, and if you’re someone who

bristles at the second half of that equation then maybe this should be

what convinces you of its truth. Exploitation is encoded into the

systems we are building, making it harder to see, harder to think and

explain, harder to counter and defend against. Not in a future of AI

overlords and robots in the factories, but right here, now, on your

screen, in your living room and in your pocket.

Many

of these latest examples confound any attempt to argue that nobody is

actually watching these videos, that these are all bots. There are

humans in the loop here, even if only on the production side, and I’m

pretty worried about them too.

I’ve

written enough, too much, but I feel like I actually need to justify

all this raving about violence and abuse and automated systems with an

example that sums it up. Maybe after everything I’ve said you won’t

think it’s so bad. I don’t know what to think any more.

[Edit, 21/11/2017:

the original video cited here has now been removed as part of YouTube’s

recent purge, although many similar videos remain on the platform. The

video used animations from the Grand Theft Auto game series overlaid

with cartoon characters assaulting, killing, and burying one another.]

This video, BURIED ALIVE Outdoor Playground Finger Family Song Nursery Rhymes Animation Education Learning Video,

contains all of the elements we’ve covered above, and takes them to

another level. Familiar characters, nursery tropes, keyword salad, full

automation, violence, and the very stuff of kids’ worst dreams. And of

course there are vast, vast numbers of these videos. Channel after channel after channel of similar content, churned out at the rate of hundreds of new videos every week. Industrialised nightmare production.

For

the final time: There is more violent and more sexual content like this

available. I’m not going to link to it. I don’t believe in traumatising

other people, but it’s necessary to keep stressing it, and not dismiss

the psychological effect on children of things which aren’t overtly

disturbing to adults, just incredibly dark and weird.

A

friend who works in digital video described to me what it would take to

make something like this: a small studio of people (half a dozen, maybe

more) making high volumes of low quality content to reap ad revenue by

tripping certain requirements of the system (length in particular seems

to be a factor). According to my friend, online kids’ content is one of

the few alternative ways of making money from 3D animation because the

aesthetic standards are lower and independent production can profit

through scale. It uses existing and easily available content (such as

character models and motion-capture libraries) and it can be repeated

and revised endlessly and mostly meaninglessly because the algorithms

don’t discriminate — and neither do the kids.

These

videos, wherever they are made, however they come to be made, and

whatever their conscious intention (i.e. to accumulate ad revenue) are

feeding upon a system which was consciously intended to show videos to

children for profit. The unconsciously-generated, emergent outcomes of

that are all over the place.

To

expose children to this content is abuse. We’re not talking about the

debatable but undoubtedly real effects of film or videogame violence on

teenagers, or the effects of pornography or extreme images on young

minds, which were alluded to in my opening description of my own teenage

internet use. Those are important debates, but they’re not what is

being discussed here. What we’re talking about is very young children,

effectively from birth, being deliberately targeted with content which

will traumatise and disturb them, via networks which are extremely

vulnerable to exactly this form of abuse. It’s not about trolls, but

about a kind of violence inherent in the combination of digital systems

and capitalist incentives. It’s down to that level of the metal.

This, I think, is my point: The system is complicit in the abuse.

And

right now, right here, YouTube and Google are complicit in that system.

The architecture they have built to extract the maximum revenue from

online video is being hacked by persons unknown to abuse children, perhaps not even deliberately,

but at a massive scale. I believe they have an absolute responsibility

to deal with this, just as they have a responsibility to deal with the

radicalisation of (mostly) young (mostly) men via extremist videos — of

any political persuasion. They have so far showed absolutely no

inclination to do this, which is in itself despicable. However, a huge

part of my troubled response to this issue is that I have no idea how

they can respond without shutting down the service itself, and most

systems which resemble it. We have built a world which operates at

scale, where human oversight is simply impossible, and no manner of

inhuman oversight will counter most of the examples I’ve used in this

essay. The asides I’ve kept in parentheses throughout, if expanded upon,

would allow one with minimal effort to rewrite everything I’ve said,

with very little effort, to be not about child abuse, but about white

nationalism, about violent religious ideologies, about fake news, about

climate denialism, about 9/11 conspiracies.

This

is a deeply dark time, in which the structures we have built to sustain

ourselves are being used against us — all of us — in systematic and

automated ways. It is hard to keep faith with the network when it

produces horrors such as these. While it is tempting to dismiss the

wilder examples as trolling, of which a significant number certainly

are, that fails to account for the sheer volume of content weighted in a

particularly grotesque direction. It presents many and complexly

entangled dangers, including that, just as with the increasing focus on

alleged Russian interference in social media, such events will be used

as justification for increased control over the internet, increasing

censorship, and so on. This is not what many of us want.

I’m going to stop here, saying only this:

What concerns me is not just the violence being done to children here, although that concerns me deeply. What

concerns me is that this is just one aspect of a kind of

infrastructural violence being done to all of us, all of the time, and

we’re still struggling to find a way to even talk about it, to describe

its mechanisms and its actions and its effects. As I said at the

beginning of this essay: this is being done by people and by things and

by a combination of things and people. Responsibility for its outcomes

is impossible to assign but the damage is very, very real indeed.

This essay forms one strand of my book New Dark Age (Verso, 2018). You can read an extract from the book, and find out more, here.

Comments

Post a Comment